Harlee ‘Gib’ Gibbons

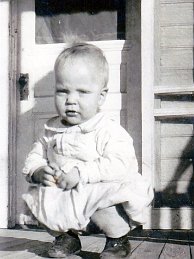

My dad, Harlee Gibbons, was named Robert James Gibbons when he was born but my grandmother changed his name on his birth certificate to Harlee, just Harlee, no middle name. No one has ever been able to tell me why. I didn’t find out about the change until after his mother had passed away.

He grew up in Jenks and you can read about that on this page and also about his time in the US Coast Guard during WWII (written by him).

He was slow to anger and seldom got really mad. He was a kind, simple man that loved his family and was willing to change when he saw reason to do so. Racism and prejudice was common in his hometown so he had to unlearn things he had been raised on. He was intelligent but underestimated himself. He had climbed the ladder in Sinclair Oil Company but gave it up because of the constant relocations so I could have consistency in my education. It was the best job he ever had for many years until he started his own company years later. We had serious games of Trivial Pursuit and he would wipe us out, especially in Geography.

You may notice that I look just like him. My mother spent two weeks in the hospital after my birth, when my dad visited the nursery, he never had to tell the nurse on duty which baby was his. He told the story of how he only ever spanked me once because I wouldn’t stop talking in a movie theater. He did the father-daughter things at church, took us to drive-in movies, water skiing and taught us to drive and not on an automatic, stick only.

My mother and I watched the daily soap opera, The Edge of Night. It came on around 4:00 in the afternoon and sometimes Dad would get home in time to see it. He always insisted he wasn’t watching and didn’t care for it but we loved to tease him when he inquired about what happened in the last episode he missed. He loved bemoaning the fact that he was outnumbered by females with his wife, two daughters and his half-sister that lived with us for many years.

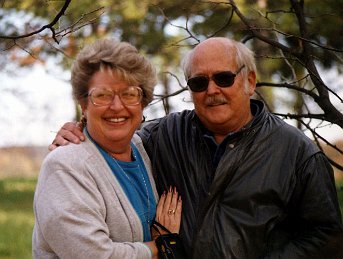

I watched him suffer through my mother’s cancer and death with dignity as he had at the loss of an infant son and my polio. He found new hope in Rosa Lee and Mitchell and discovered Little League and Tupperware along the way. Dad and Rosa Lee planned to marry just a little over a year after my mother’s death and I was feeling resistant. A dear friend of my mother’s told me that it was a compliment to my mother that he was remarrying so soon and I realized that was true. He was a man that liked being married. They married in February of 1971 and were married for 30 years until he passed away on September 24, 2001.

He grew up in Jenks and you can read about that on this page and also about his time in the US Coast Guard during WWII (written by him).

He was slow to anger and seldom got really mad. He was a kind, simple man that loved his family and was willing to change when he saw reason to do so. Racism and prejudice was common in his hometown so he had to unlearn things he had been raised on. He was intelligent but underestimated himself. He had climbed the ladder in Sinclair Oil Company but gave it up because of the constant relocations so I could have consistency in my education. It was the best job he ever had for many years until he started his own company years later. We had serious games of Trivial Pursuit and he would wipe us out, especially in Geography.

You may notice that I look just like him. My mother spent two weeks in the hospital after my birth, when my dad visited the nursery, he never had to tell the nurse on duty which baby was his. He told the story of how he only ever spanked me once because I wouldn’t stop talking in a movie theater. He did the father-daughter things at church, took us to drive-in movies, water skiing and taught us to drive and not on an automatic, stick only.

My mother and I watched the daily soap opera, The Edge of Night. It came on around 4:00 in the afternoon and sometimes Dad would get home in time to see it. He always insisted he wasn’t watching and didn’t care for it but we loved to tease him when he inquired about what happened in the last episode he missed. He loved bemoaning the fact that he was outnumbered by females with his wife, two daughters and his half-sister that lived with us for many years.

I watched him suffer through my mother’s cancer and death with dignity as he had at the loss of an infant son and my polio. He found new hope in Rosa Lee and Mitchell and discovered Little League and Tupperware along the way. Dad and Rosa Lee planned to marry just a little over a year after my mother’s death and I was feeling resistant. A dear friend of my mother’s told me that it was a compliment to my mother that he was remarrying so soon and I realized that was true. He was a man that liked being married. They married in February of 1971 and were married for 30 years until he passed away on September 24, 2001.

Growing up in Jenks, Oklahoma

The farm house where I was born was on property that is now Oral Roberts University. The structure they call the prayer tower is built about where the old farm house was. I tell people that it was built as a monument to my birthplace.

I had two brothers. Harvey, who was ten years older than me and Marshall or “Bunk”, as he was known in Jenks. Harvey was 24-years-old when he was killed in an accident working on a pipeline construction job in Kansas. Bunk worked for Arco Oil out in western Oklahoma and retired at age 65. He died 2 years later when they were living in Hot Springs, Arkansas. I’m not sure, but I think he died in 1985 of lung cancer and acute alcoholism.

When I was five years old, my dad took a job as caretaker of a Catholic cemetery that was about 2 miles from Jenks. My first school was Haikey School. It was a 2-room building and had all grades 1 thru 8. Haikey was the name of an Indian family who lived in the area. After my fifth-grade-year Haikey consolidated with Jenks. The best part of that was, I didn’t have to walk to school. We now had buses.

My cousin Annabel and I were in the same grade at Haikey School. We occasionally spent the night at each others house. This particular time I was going home with her just happened to be when ex-lax was first out for sale. They had sent samples in the mail to everyone. We raided the mail boxes on the way to her house and got a lot of that “chocolate candy”. We ate a lot of it that night and it started paying off on the way to school the next day. She took to the ditch on one side of the road and I, the other. That was a bad day.

When I was seven, the Ed Bolt family moved about a mile from us. They had a son named Bill. He and I became close friends and stayed in touch until Bill died in 1991. We were separated for long periods of time, but somehow would always manage to get back together again.

One summer, Bill and I decided to steal a watermelon from my neighbors who lived across the road. We sneaked into the field, found the melon, busted it open and ate all we wanted. But as we walked away, someone shot at us with a shotgun. We both took off running as fast as we could. When we ran out of flat ground we jumped off a cliff about 20 feet high. We just dove off head first. Luckily, we landed ok, but we were plenty scared.

Those neighbors were a Black family by the last name of Douglas. Doug, the husband that shot at us, had served time for killing a man. His wife was a lady named Georgia. They didn’t have any kids, but she had a nephew about my age. I don’t recall his name. We played together some when Bill was not around. One time he and I were scuffling and he said, “Boy I’m gonna whip your a__.” Then we really did have a fight. I don’t even recall who won. Doug never did mention anything about shooting at us. I expect he fired up in the air just to scare us. If so, he sure succeeded.

For the most part, the next few years were uneventful. Then came the depression. Those were the days when many families went hungry. We were very fortunate. Dad’s job as caretaker of what is now known as Calvary Cemetery at 91st and Harvard didn’t change at all. He still drew the same wages, had a three-bed room-house furnished and had about 100 acres of land that we could farm and raise cows and pigs. I worked every summer in the cemetery for my dad. I didn’t get paid either. I pushed lawnmowers and dug graves.

It was an annual tradition to have a Junior vs Senior fist fight. This would occur during the Queen Race and Basketball Season. Seniors would line up on one side of main street, juniors on the other. When some one would give the signal, each side would walk to the black line in the middle of the street and duke it out with who ever you met. The year I was a junior, there was a boy named Francis Hogan who was a senior. I worked my way around to where I thought I would meet Francis. I thought that since he was smaller than me he would be easy. Not so, Francis just gave me a good whipping. I think there is a lesson to be learned there.

When I was about 15 years old Bunk and I pooled our money, eighteen dollars each, and bought a 1927 Model-T ford. Bunk was always borrowing money from me a few dollars at a time. He didn’t like to work and I was caddying at Southern Hills Country Club. After he had borrowed eighteen dollars from me, I foreclosed on him and took his half of the Ford. It was my Ford then and he never set foot in it again.

There was one thing wrong with that old car, about once a week you had to get under it and straighten the radius rod. After driving the car for a while the rod would become bent and the steering wheel would turn, but the front wheels wouldn’t.

One day after caddying at Southern Hills, I loaded up with caddys going back to Jenks. The main gate to the country club was at the bottom of a long hill where you had to make a sharp turn. When I turned the steering wheel to the left, it turned, but the front wheels didn’t. I went through a ditch, a three-wire fence and stopped out in a farmer’s corn field. I had to crawl under the car and push with both feet to straighten the radius rod. I had plenty of help from those caddys pushing the car out of the field and then we went on to Jenks. I drove that car a lot of miles. I can’t remember what happened to it, but I think it probably was a pile of junk.

W. K. Warren was president and major stockholder of Warren Petroleum Co.in Tulsa. He was a philanthrophist and a major contributor to St. Francis Hospital and other medical facilities in Tulsa. He was also a member of Southern Hills Country Club and a First Class S.O.B., that would verbally abuse a caddy. Most of us would just take it with a grain of salt, but not Ralph James. The first time Ralph was his caddy, he waited until they were at the farthest point from the clubhouse then threw down his bag and clubs and told him, “carry them yourself, you S.O.B. Needless to say, that was the end of Ralph’s career as a caddy at Southern Hills.

The city of Jenks had a law against shooting fireworks inside the city limits. They also had a City Marshall named Harlan Bolton. Bill Bolt, myself and two more fellows would all four throw as many firecrackers as we could out in the middle of Main Street at the end of the block. When Harlan would run down to see what was happening, we would run down the alley to the other end of the block and throw out some more. We did this over and over until Harlan finally got wise to what we were doing. Then he hid in the doorway of a store and stayed there until we got back. We thought he was at the other end of the street when he grabbed me by the collar and threw me in jail.

After he put me in jail, Harlan went home to bed and I was in there by myself. There was no glass in the cell window, just bars. Inside there were three bunks and a toilet. Bill and the others handed firecrackers through the window bars to me. Then I would throw the fireworks in the toilet where they sounded a lot louder than normal. We kept this up until we ran out of fireworks. The mayors house was just across the street from the jail and he was quite put out about his lack of sleep that night.

Harlan got me the next morning and bought my breakfast. Then I had to go before Judge Fisher and he fined me three dollars. My dad was there. He didn’t get excited about it. Just paid my fine and took me home. I was probably about 14 years old then.

About 1938 was when things got bad. My mother and dad finally ended up in a divorce in my junior year at Jenks High School. Things were so messed up I flunked my senior year. But I wanted that diploma so badly that I went to the principal after school was out and asked him what I could do to graduate mid-term the next year. We agreed that I would come back and finish 12 weeks of the first semester. Believe it or not, I did and got my diploma.

I would work summers for my cousin, Harold Stunkard, driving trucks and loading and unloading. When I was back in school to get my diploma, I lived part of the time with Harold and Dorothy. He and Dorothy are the only ones that came to my graduation.

After my parents were divorced, dad married a young, 19-year-old girl named Hope. They had a daughter, my half-sister, named Carol Ann. My mother went to work for the housekeeping department at St Johns Hospital. I worked at the farmers market loading and unloading trucks. I spent lots of nights sleeping in the back of a truck. After I got my diploma, I went to work for Harold Stunkard. Eventually I was old enough to get a chauffer’s license and then I drove one of his trucks.

After the war, I worked on pipeline construction jobs in Pennsylvania, Colorado and Texas. One time, when I was home between jobs, I became aware of Shirley Lemke. I had known her since she was six years old. We dated while I was in town and then I had to go to Colorado to work. When that job was over I was going to a job in Beeville, Texas. In route to Beeville, I stopped for a week in Tulsa. Shirley and I had been writing all the time I was in Colorado. We found a justice of the peace and got married Saturday night, then left Monday morning for Texas.

I’ve always regretted that Shirley and I eloped. It hurt Don and Gertsie more than we thought. They could not have been better in-laws to me. Shirley was one of those girls that didn’t learn much about cooking and housekeeping at home or in school. When we moved to Taft, Texas she started learning. A little late, but she eventually became a good cook.

When I was working on a pipeline job as an inspector in Colorado, the contractor would come around every Friday and give all the inspectors a fifth of whiskey. I didn’t drink much of it, just put it in a box in the trunk of my car. When I went home after the job was finished I put all the bottles in the kitchen under the sink. Sometime later, I decided to have a snort and it was all gone. Shirley and Don had been dipping in to my booze.

Shirley wasn’t a heavy drinker, but Don might be called one. Shirley’s Grandpa, Joe Havlik, was a heavy drinker and when he got so old he couldn’t get to a liquor store, Gertsie wouldn’t allow him to have any booze. He would come to our house in Copan and stay as long as he could, because Shirley would go to the pool hall every day and get him a six pack of beer. The pool hall was the only place that sold beer. It was not the nicest place in town so she would get in and out as fast as she could.

It was a good marriage and produced two fine daughters, Cathy and Merry Beth. There was also a son named Michael David. He only lived one day. He had a heart condition that could be corrected today in a simple operation.

Before Cathy was born I decided that bumming around the country on pipeline construction work was not the best deal for a family man. I applied for a job with Sinclair Pipeline. We had been working on one of their pipelines. I was hired on as a truck driver at Luling, Texas. Cathy was born in Luling.

Gertsie, Shirley’s mother, came down to Luling to see after Shirley and Cathy since she was born by Cesearean section. Shirley and Gertsie were getting cabin fever staying inside. When Shirley began feeling better I told them to go to the movies. I assured them I could take care of the kid and change diapers. Everything was ok until just before they got back. I had changed her diaper, but couldn’t get the safety pin in on one side. Cathy was crying her head off as Shirley got home. That’s when I found out I had been trying to pin her belly to the diaper. Needless to say, I got some lessons in childcare.

Christmas was a very important time for Shirley. She would go all out for Cathy and Merry Beth and her brother, David Lemke’s kids. The kids had a great Christmas no matter what. I might be in hock for the rest of the year, but so what, we had a good Christmas.

Later we transferred to Corpus Christi, Texas and finally to Copan, Okla. Where I was a pump station engineer and where we stayed until 1953. In 1951, we had a major setback when Cathy got real sick and it turned out to be sleeping sickness, spinal polio and bulbar polio. She was three-years-old and was hospitalized at St Johns Hospital in Tulsa. She was the sickest child there that year that didn’t die. Thanks to God, Dr. White and Miss Cool, her physical therapist, she had no lasting effects of the illnesses.

My maternal grandparents were named Marshall. Grandma Marshall, (Paulina Goodwin Marshall) died before I was born. I only remember seeing Grandpa Marshall one time and that is all I remember about him.

My paternal grandparents were Allen and Anna Gibbons. I don’t remember much about him except that he had a beard and I liked him. Grandma Gibbons was born Anna Luther in the state of Virginia. She and grandpa were married in Brazil, Indiana. Her parents owned slaves when she was a little girl. When I was little she used to tell me stories about slaves and things they did. I was just a little kid then and don’t remember the stories she told.

Grandma was the sweetest old lady. After grandpa died she lived with us. She was very cold natured and, when the weather got cool in the fall, she would insist that I sleep with her. When it really got cold, she would put two bricks on the wood stove to warm. About half an hour before bed time, when the bricks were warm enough, she would wrap them in towels and put them in her bed to warm it up. But I still had to go to bed when she did. —Harlee Gibbons

I had two brothers. Harvey, who was ten years older than me and Marshall or “Bunk”, as he was known in Jenks. Harvey was 24-years-old when he was killed in an accident working on a pipeline construction job in Kansas. Bunk worked for Arco Oil out in western Oklahoma and retired at age 65. He died 2 years later when they were living in Hot Springs, Arkansas. I’m not sure, but I think he died in 1985 of lung cancer and acute alcoholism.

When I was five years old, my dad took a job as caretaker of a Catholic cemetery that was about 2 miles from Jenks. My first school was Haikey School. It was a 2-room building and had all grades 1 thru 8. Haikey was the name of an Indian family who lived in the area. After my fifth-grade-year Haikey consolidated with Jenks. The best part of that was, I didn’t have to walk to school. We now had buses.

My cousin Annabel and I were in the same grade at Haikey School. We occasionally spent the night at each others house. This particular time I was going home with her just happened to be when ex-lax was first out for sale. They had sent samples in the mail to everyone. We raided the mail boxes on the way to her house and got a lot of that “chocolate candy”. We ate a lot of it that night and it started paying off on the way to school the next day. She took to the ditch on one side of the road and I, the other. That was a bad day.

When I was seven, the Ed Bolt family moved about a mile from us. They had a son named Bill. He and I became close friends and stayed in touch until Bill died in 1991. We were separated for long periods of time, but somehow would always manage to get back together again.

One summer, Bill and I decided to steal a watermelon from my neighbors who lived across the road. We sneaked into the field, found the melon, busted it open and ate all we wanted. But as we walked away, someone shot at us with a shotgun. We both took off running as fast as we could. When we ran out of flat ground we jumped off a cliff about 20 feet high. We just dove off head first. Luckily, we landed ok, but we were plenty scared.

Those neighbors were a Black family by the last name of Douglas. Doug, the husband that shot at us, had served time for killing a man. His wife was a lady named Georgia. They didn’t have any kids, but she had a nephew about my age. I don’t recall his name. We played together some when Bill was not around. One time he and I were scuffling and he said, “Boy I’m gonna whip your a__.” Then we really did have a fight. I don’t even recall who won. Doug never did mention anything about shooting at us. I expect he fired up in the air just to scare us. If so, he sure succeeded.

For the most part, the next few years were uneventful. Then came the depression. Those were the days when many families went hungry. We were very fortunate. Dad’s job as caretaker of what is now known as Calvary Cemetery at 91st and Harvard didn’t change at all. He still drew the same wages, had a three-bed room-house furnished and had about 100 acres of land that we could farm and raise cows and pigs. I worked every summer in the cemetery for my dad. I didn’t get paid either. I pushed lawnmowers and dug graves.

It was an annual tradition to have a Junior vs Senior fist fight. This would occur during the Queen Race and Basketball Season. Seniors would line up on one side of main street, juniors on the other. When some one would give the signal, each side would walk to the black line in the middle of the street and duke it out with who ever you met. The year I was a junior, there was a boy named Francis Hogan who was a senior. I worked my way around to where I thought I would meet Francis. I thought that since he was smaller than me he would be easy. Not so, Francis just gave me a good whipping. I think there is a lesson to be learned there.

When I was about 15 years old Bunk and I pooled our money, eighteen dollars each, and bought a 1927 Model-T ford. Bunk was always borrowing money from me a few dollars at a time. He didn’t like to work and I was caddying at Southern Hills Country Club. After he had borrowed eighteen dollars from me, I foreclosed on him and took his half of the Ford. It was my Ford then and he never set foot in it again.

There was one thing wrong with that old car, about once a week you had to get under it and straighten the radius rod. After driving the car for a while the rod would become bent and the steering wheel would turn, but the front wheels wouldn’t.

One day after caddying at Southern Hills, I loaded up with caddys going back to Jenks. The main gate to the country club was at the bottom of a long hill where you had to make a sharp turn. When I turned the steering wheel to the left, it turned, but the front wheels didn’t. I went through a ditch, a three-wire fence and stopped out in a farmer’s corn field. I had to crawl under the car and push with both feet to straighten the radius rod. I had plenty of help from those caddys pushing the car out of the field and then we went on to Jenks. I drove that car a lot of miles. I can’t remember what happened to it, but I think it probably was a pile of junk.

W. K. Warren was president and major stockholder of Warren Petroleum Co.in Tulsa. He was a philanthrophist and a major contributor to St. Francis Hospital and other medical facilities in Tulsa. He was also a member of Southern Hills Country Club and a First Class S.O.B., that would verbally abuse a caddy. Most of us would just take it with a grain of salt, but not Ralph James. The first time Ralph was his caddy, he waited until they were at the farthest point from the clubhouse then threw down his bag and clubs and told him, “carry them yourself, you S.O.B. Needless to say, that was the end of Ralph’s career as a caddy at Southern Hills.

The city of Jenks had a law against shooting fireworks inside the city limits. They also had a City Marshall named Harlan Bolton. Bill Bolt, myself and two more fellows would all four throw as many firecrackers as we could out in the middle of Main Street at the end of the block. When Harlan would run down to see what was happening, we would run down the alley to the other end of the block and throw out some more. We did this over and over until Harlan finally got wise to what we were doing. Then he hid in the doorway of a store and stayed there until we got back. We thought he was at the other end of the street when he grabbed me by the collar and threw me in jail.

After he put me in jail, Harlan went home to bed and I was in there by myself. There was no glass in the cell window, just bars. Inside there were three bunks and a toilet. Bill and the others handed firecrackers through the window bars to me. Then I would throw the fireworks in the toilet where they sounded a lot louder than normal. We kept this up until we ran out of fireworks. The mayors house was just across the street from the jail and he was quite put out about his lack of sleep that night.

Harlan got me the next morning and bought my breakfast. Then I had to go before Judge Fisher and he fined me three dollars. My dad was there. He didn’t get excited about it. Just paid my fine and took me home. I was probably about 14 years old then.

About 1938 was when things got bad. My mother and dad finally ended up in a divorce in my junior year at Jenks High School. Things were so messed up I flunked my senior year. But I wanted that diploma so badly that I went to the principal after school was out and asked him what I could do to graduate mid-term the next year. We agreed that I would come back and finish 12 weeks of the first semester. Believe it or not, I did and got my diploma.

I would work summers for my cousin, Harold Stunkard, driving trucks and loading and unloading. When I was back in school to get my diploma, I lived part of the time with Harold and Dorothy. He and Dorothy are the only ones that came to my graduation.

After my parents were divorced, dad married a young, 19-year-old girl named Hope. They had a daughter, my half-sister, named Carol Ann. My mother went to work for the housekeeping department at St Johns Hospital. I worked at the farmers market loading and unloading trucks. I spent lots of nights sleeping in the back of a truck. After I got my diploma, I went to work for Harold Stunkard. Eventually I was old enough to get a chauffer’s license and then I drove one of his trucks.

After the war, I worked on pipeline construction jobs in Pennsylvania, Colorado and Texas. One time, when I was home between jobs, I became aware of Shirley Lemke. I had known her since she was six years old. We dated while I was in town and then I had to go to Colorado to work. When that job was over I was going to a job in Beeville, Texas. In route to Beeville, I stopped for a week in Tulsa. Shirley and I had been writing all the time I was in Colorado. We found a justice of the peace and got married Saturday night, then left Monday morning for Texas.

I’ve always regretted that Shirley and I eloped. It hurt Don and Gertsie more than we thought. They could not have been better in-laws to me. Shirley was one of those girls that didn’t learn much about cooking and housekeeping at home or in school. When we moved to Taft, Texas she started learning. A little late, but she eventually became a good cook.

When I was working on a pipeline job as an inspector in Colorado, the contractor would come around every Friday and give all the inspectors a fifth of whiskey. I didn’t drink much of it, just put it in a box in the trunk of my car. When I went home after the job was finished I put all the bottles in the kitchen under the sink. Sometime later, I decided to have a snort and it was all gone. Shirley and Don had been dipping in to my booze.

Shirley wasn’t a heavy drinker, but Don might be called one. Shirley’s Grandpa, Joe Havlik, was a heavy drinker and when he got so old he couldn’t get to a liquor store, Gertsie wouldn’t allow him to have any booze. He would come to our house in Copan and stay as long as he could, because Shirley would go to the pool hall every day and get him a six pack of beer. The pool hall was the only place that sold beer. It was not the nicest place in town so she would get in and out as fast as she could.

It was a good marriage and produced two fine daughters, Cathy and Merry Beth. There was also a son named Michael David. He only lived one day. He had a heart condition that could be corrected today in a simple operation.

Before Cathy was born I decided that bumming around the country on pipeline construction work was not the best deal for a family man. I applied for a job with Sinclair Pipeline. We had been working on one of their pipelines. I was hired on as a truck driver at Luling, Texas. Cathy was born in Luling.

Gertsie, Shirley’s mother, came down to Luling to see after Shirley and Cathy since she was born by Cesearean section. Shirley and Gertsie were getting cabin fever staying inside. When Shirley began feeling better I told them to go to the movies. I assured them I could take care of the kid and change diapers. Everything was ok until just before they got back. I had changed her diaper, but couldn’t get the safety pin in on one side. Cathy was crying her head off as Shirley got home. That’s when I found out I had been trying to pin her belly to the diaper. Needless to say, I got some lessons in childcare.

Christmas was a very important time for Shirley. She would go all out for Cathy and Merry Beth and her brother, David Lemke’s kids. The kids had a great Christmas no matter what. I might be in hock for the rest of the year, but so what, we had a good Christmas.

Later we transferred to Corpus Christi, Texas and finally to Copan, Okla. Where I was a pump station engineer and where we stayed until 1953. In 1951, we had a major setback when Cathy got real sick and it turned out to be sleeping sickness, spinal polio and bulbar polio. She was three-years-old and was hospitalized at St Johns Hospital in Tulsa. She was the sickest child there that year that didn’t die. Thanks to God, Dr. White and Miss Cool, her physical therapist, she had no lasting effects of the illnesses.

My maternal grandparents were named Marshall. Grandma Marshall, (Paulina Goodwin Marshall) died before I was born. I only remember seeing Grandpa Marshall one time and that is all I remember about him.

My paternal grandparents were Allen and Anna Gibbons. I don’t remember much about him except that he had a beard and I liked him. Grandma Gibbons was born Anna Luther in the state of Virginia. She and grandpa were married in Brazil, Indiana. Her parents owned slaves when she was a little girl. When I was little she used to tell me stories about slaves and things they did. I was just a little kid then and don’t remember the stories she told.

Grandma was the sweetest old lady. After grandpa died she lived with us. She was very cold natured and, when the weather got cool in the fall, she would insist that I sleep with her. When it really got cold, she would put two bricks on the wood stove to warm. About half an hour before bed time, when the bricks were warm enough, she would wrap them in towels and put them in her bed to warm it up. But I still had to go to bed when she did. —Harlee Gibbons

Service Diary-Harlee Gibbons, 1942-1944

Disclaimer: this is his story about what he did and saw during the war, may not be appropriate for everyone.

USS PC 590, 1942 and 1943

After our shake down cruise we found ourselves at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Our first assignment was to escort an antique English freighter to Kingston, Jamaica. That old freighter had a top speed of 3 knots and the boilers were fired by coal. You could see the black smoke for miles and miles. The Caribbean was lousy with German U-boats. How they missed seeing us was a miracle. Maybe they didn’t think we were worth wasting a torpedo on. It took about ten days to get there. The freighter was so slow that we just ran around it in circles. We knew we were going to get torpedoed, but we lucked out.

We did not even get to go ashore in Jamaica. Then we got orders to go to the Panama Canal. We went through the canal to a town on the Pacific side called Balboa. There was plenty of rum and coca-cola. I felt real bad the next morning. I had mess cook duty that day. We were cooking greasy pork chops for lunch and that was the first and only time I ever got seasick.

We then went on to San Diego and then to Pearl Harbor where we were on submarine patrol until an escort job came up. We would escort merchant ships to Midway Island, where the famous Battle of Midway was fought a few months earlier. While we were there it was rumored that the Japs were headed back to try it again. The army sent several B24 bombers there, just in case, but they never did show up.

Wake Island was a Japanese occupied island about four or five hundred miles west of Midway. They would send a submarine out one mile from wake and send us half way to wake. Our job was to pick up any fliers that were knocked down.

One of the B24s got hit pretty good. The bombardier, who sits out in the nose of it was killed. Their gas tanks were hit and they lost most of their gas. They made it back to our vicinity and landed in the water doing 100mph. The B24 broke up and sank. The bombardier went down with the plane and the other four men made it into a rubber lifeboat. They had radioed their position to Midway and then Midway radioed us. It took about four hours to get to them. They were broken and bleeding, all in pretty bad shape. The blood was running in the water and sharks were all around them. It was about 11pm and dark, but we managed to get them on board. They were so badly hurt that we could not take them below deck. We didn’t have a doctor on board, but we did have a pharmacist’s mate whose name was Mike Schmookler. He patched those guys up as best he could and they all survived. Mike ran onto them later in Honolulu and they wined and dined him real good.

We spent a lot of the first year escorting merchant ships to places like the Johnson Islands, Christmas Island, Maui and Hilo in the Hawaiian Islands. But mostly we were in Midway and on sub patrol while we waited for another ship to escort back to Pearl Harbor.

One trip, Pearl Harbor, I won’t forget. The old man ran us aground going through the channel to Midway. It punched a hole in the bottom of the ship, bent both shafts, both propellers and both rudders. We were towed back to Pearl behind a slow freighter on a Hauser (rope) about fifty yards long. The sea was rough and that was one hell of a ride.

While on sub patrol at Midway we got a sonar contact and dropped depth charges. We never did see the sub but debris came to the surface. I will always believe we sank it, but we never did get credit for it.

I bought a fish hook in Honolulu that was made out of steel about a quarter inch in diameter. While we were on patrol at the entrance to Pearl Harbor I got a chunk of beef that probably weighed five pounds and trailed it behind the ship on a long rope and luckily caught a shark about eight feet long. I pulled him up along side the ship, then I didn’t know what to do with him. Finally, the old man brought out a rifle and shot him for me. I cut the shark’s head off and cleaned all the meat off the jawbone. The teeth really cut my hands up cleaning that jawbone. Next, I salted it real good and put it up on top of the mast to dry in the sun. A few days later I went to get it and it was gone. Some so and so stole my shark jaws.

One of our guys was a man named Hugh Jones. Jonesy never took a bath. He worked in the engine room where it was very hot and he would sweat a lot. Needless to say, Jonesy smelled pretty bad. One night when two more men and I got off watch at midnight, there he was asleep on his top bunk, buck naked and you could smell him before you got there. We tied a string around his tally whacker, tied the other end to one of his shoes and threw it over some overhead pipes. We just ran and didn’t stay around to see the fun. Nothing was ever said about it by Jonesy.

Midway Island is probably the most worthless piece of real estate in the Pacific. Nothing there but sand, goony birds and a few seals. The Navy had a few small buildings, a small group of sailors, a landing strip, a control tower and a pier with enough room for two ships to tie up. We were tied up at one pier with a sub in front of us and there was a large sub tender across from us.

I knew that Troy Price, a guy from Jenks, was a torpedo man on a sub. I had no idea where he was but thought it was worth asking the guard on duty on the sub if he knew him. He said, “yes, he is down in the torpedo room.” He showed me how to get there and there was Troy sitting on a five gallon can of torpedo juice. Torpedo juice is some kind of alcohol that runs the engine on a torpedo. Troy and two more guys were drinking the stuff. He poured me a cup of it, but I couldn’t handle it. Troy was just four years older than me and his hair had already turned white.

The next day the sub tender was holding muster and I saw one man with the name “Wildey” stenciled on the back of his shirt. It was Jack Wildey, one of my classmates at Jenks High School. Jack, Troy and I went up to the Navy Base where they had a lot of cold beer and we had a Jenks reunion right there on Midway.

I wonder what the odds are that three guys from Jenks, Oklahoma would meet up on a God forsaken place like Midway Island. That was the last time either one of those guys saw anyone from home. Jack got transferred to a sub and both he and Troy were killed when their subs were sunk by the Japs.

That is about all from the PC 590 and Midway. The chief engineer on the 590 and I did not get along, one day I got pissed off and requested a transfer. That was the beginning of my tour of duty on the LST 23.

USS LCV 23, 1943 and 1944

An LCV is 300-feet-long with bow doors that open up and a ramp comes down for loading and unloading tanks, trucks, jeeps or any type of vehicle. It has one three-inch gun, two forty-millimeter, and four twenty-millimeter anti-aircraft guns. It had four LCVP boats that could be lowered down to the ocean. LCVP stands for landing craft vehicle personnel. I was assigned to one as engineer and machine gunner. I manned a thirty-caliber air cooled machine gun on the stern in a swivel mount. You get in the center of it and it will turn 360 degrees. I stood watches in the engine room while we were underway and when we were making a landing I manned the thirty-caliber.

Our first trip was to a couple of islands called Funifuti and Nukifutu where we waited for a transport. When it finally came, we loaded 200 marines of the 22nd Marine anti craft batallion, their guns, trucks and equipment of all kinds onto the LST. We didn’t know where we would be taking them until we were under way.

After several days at sea we woke up one morning and there were ships of all kinds everywhere we looked. It was all big stuff so we knew that something big was coming up. These jarhead marines we had on board were typical marines. They bragged about how good they were with their anti-aircraft guns. We put them ashore and they set up their AA guns.

Tarawa was the toughest battle that we had had. There were one thousand and twenty six of our men killed plus many more wounded. There were 5,000 Japanese killed and only 18 taken prisoner. Our men were buried right away. Three days after the battle ended, the old man had to go ashore for some reason. My boat took him in and the stench of those rotting Japanese bodies that had been lying in the hot sun for three days was something I’ll never forget.

They dug a ditch with a bull dozer about 150 yards long and about 10 feet wide, then pushed all the dead Japs in it with the bull dozer. That afternoon we loaded 400 drums of high octane aviation gasoline on board. We beached the ship just as it was getting dark and had to wait until the next morning to unload it. That night about ten o’clock they sounded general quarters, the radar had picked up enemy bombers coming in. They would not let us fire our guns to keep from giving away our position all we could do was sit there and take it. If we had been hit with that four hundred drums of gas, it would have roasted us good. Our friends, the Marine Antiaircraft guys, got a good work out. They fired no telling how many rounds of ammo and never did hit one of the enemy. The next day when we asked them what happened, they admitted that their radar was calibrated 1000 yards off. They were firing behind them.

We stayed there for several days unloading freighters that could only anchor in the harbor. One of them had hundreds of cases of pineapple juice. I forget the guys name, but he and I stole several cases. We hid them in a void space that was sealed off. We filled a large glass bottle about three quarters full of pineapple juice, added enough sugar to almost fill it and then we sealed it and left it in the void space. About 3 weeks later we decided it should be ready. When we opened the void space, the fermenting stuff had built up pressure and the odor of the stuff floated back to the Crews Quarters. Those guys smelled it and followed their noses to where we were and, boy, did we have a party.

We finally loaded the survivors of the Second Marine amphibious and what was left of their equipment and took them to Hilo on the big island of Hawaii. We then went back to Pearl Harbor where we loaded men and equipment for what we later found to be Kwajelin in the Marshall Islands. The island is maybe 4 miles long and crescent shaped. We beached about the center of the island and had to stay there. There was a small island directly behind us where the army set up 105 mm howitzers that fired just over our heads. You had to duck every time one of them went over. Luckily they never did hit us. I later found out that it was my brother, Bunk’s 48th field artillery that was over there doing all the firing. I would have been really scared if I had known he had anything to do with it. —Harlee Gibbons

USS PC 590, 1942 and 1943

After our shake down cruise we found ourselves at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Our first assignment was to escort an antique English freighter to Kingston, Jamaica. That old freighter had a top speed of 3 knots and the boilers were fired by coal. You could see the black smoke for miles and miles. The Caribbean was lousy with German U-boats. How they missed seeing us was a miracle. Maybe they didn’t think we were worth wasting a torpedo on. It took about ten days to get there. The freighter was so slow that we just ran around it in circles. We knew we were going to get torpedoed, but we lucked out.

We did not even get to go ashore in Jamaica. Then we got orders to go to the Panama Canal. We went through the canal to a town on the Pacific side called Balboa. There was plenty of rum and coca-cola. I felt real bad the next morning. I had mess cook duty that day. We were cooking greasy pork chops for lunch and that was the first and only time I ever got seasick.

We then went on to San Diego and then to Pearl Harbor where we were on submarine patrol until an escort job came up. We would escort merchant ships to Midway Island, where the famous Battle of Midway was fought a few months earlier. While we were there it was rumored that the Japs were headed back to try it again. The army sent several B24 bombers there, just in case, but they never did show up.

Wake Island was a Japanese occupied island about four or five hundred miles west of Midway. They would send a submarine out one mile from wake and send us half way to wake. Our job was to pick up any fliers that were knocked down.

One of the B24s got hit pretty good. The bombardier, who sits out in the nose of it was killed. Their gas tanks were hit and they lost most of their gas. They made it back to our vicinity and landed in the water doing 100mph. The B24 broke up and sank. The bombardier went down with the plane and the other four men made it into a rubber lifeboat. They had radioed their position to Midway and then Midway radioed us. It took about four hours to get to them. They were broken and bleeding, all in pretty bad shape. The blood was running in the water and sharks were all around them. It was about 11pm and dark, but we managed to get them on board. They were so badly hurt that we could not take them below deck. We didn’t have a doctor on board, but we did have a pharmacist’s mate whose name was Mike Schmookler. He patched those guys up as best he could and they all survived. Mike ran onto them later in Honolulu and they wined and dined him real good.

We spent a lot of the first year escorting merchant ships to places like the Johnson Islands, Christmas Island, Maui and Hilo in the Hawaiian Islands. But mostly we were in Midway and on sub patrol while we waited for another ship to escort back to Pearl Harbor.

One trip, Pearl Harbor, I won’t forget. The old man ran us aground going through the channel to Midway. It punched a hole in the bottom of the ship, bent both shafts, both propellers and both rudders. We were towed back to Pearl behind a slow freighter on a Hauser (rope) about fifty yards long. The sea was rough and that was one hell of a ride.

While on sub patrol at Midway we got a sonar contact and dropped depth charges. We never did see the sub but debris came to the surface. I will always believe we sank it, but we never did get credit for it.

I bought a fish hook in Honolulu that was made out of steel about a quarter inch in diameter. While we were on patrol at the entrance to Pearl Harbor I got a chunk of beef that probably weighed five pounds and trailed it behind the ship on a long rope and luckily caught a shark about eight feet long. I pulled him up along side the ship, then I didn’t know what to do with him. Finally, the old man brought out a rifle and shot him for me. I cut the shark’s head off and cleaned all the meat off the jawbone. The teeth really cut my hands up cleaning that jawbone. Next, I salted it real good and put it up on top of the mast to dry in the sun. A few days later I went to get it and it was gone. Some so and so stole my shark jaws.

One of our guys was a man named Hugh Jones. Jonesy never took a bath. He worked in the engine room where it was very hot and he would sweat a lot. Needless to say, Jonesy smelled pretty bad. One night when two more men and I got off watch at midnight, there he was asleep on his top bunk, buck naked and you could smell him before you got there. We tied a string around his tally whacker, tied the other end to one of his shoes and threw it over some overhead pipes. We just ran and didn’t stay around to see the fun. Nothing was ever said about it by Jonesy.

Midway Island is probably the most worthless piece of real estate in the Pacific. Nothing there but sand, goony birds and a few seals. The Navy had a few small buildings, a small group of sailors, a landing strip, a control tower and a pier with enough room for two ships to tie up. We were tied up at one pier with a sub in front of us and there was a large sub tender across from us.

I knew that Troy Price, a guy from Jenks, was a torpedo man on a sub. I had no idea where he was but thought it was worth asking the guard on duty on the sub if he knew him. He said, “yes, he is down in the torpedo room.” He showed me how to get there and there was Troy sitting on a five gallon can of torpedo juice. Torpedo juice is some kind of alcohol that runs the engine on a torpedo. Troy and two more guys were drinking the stuff. He poured me a cup of it, but I couldn’t handle it. Troy was just four years older than me and his hair had already turned white.

The next day the sub tender was holding muster and I saw one man with the name “Wildey” stenciled on the back of his shirt. It was Jack Wildey, one of my classmates at Jenks High School. Jack, Troy and I went up to the Navy Base where they had a lot of cold beer and we had a Jenks reunion right there on Midway.

I wonder what the odds are that three guys from Jenks, Oklahoma would meet up on a God forsaken place like Midway Island. That was the last time either one of those guys saw anyone from home. Jack got transferred to a sub and both he and Troy were killed when their subs were sunk by the Japs.

That is about all from the PC 590 and Midway. The chief engineer on the 590 and I did not get along, one day I got pissed off and requested a transfer. That was the beginning of my tour of duty on the LST 23.

USS LCV 23, 1943 and 1944

An LCV is 300-feet-long with bow doors that open up and a ramp comes down for loading and unloading tanks, trucks, jeeps or any type of vehicle. It has one three-inch gun, two forty-millimeter, and four twenty-millimeter anti-aircraft guns. It had four LCVP boats that could be lowered down to the ocean. LCVP stands for landing craft vehicle personnel. I was assigned to one as engineer and machine gunner. I manned a thirty-caliber air cooled machine gun on the stern in a swivel mount. You get in the center of it and it will turn 360 degrees. I stood watches in the engine room while we were underway and when we were making a landing I manned the thirty-caliber.

Our first trip was to a couple of islands called Funifuti and Nukifutu where we waited for a transport. When it finally came, we loaded 200 marines of the 22nd Marine anti craft batallion, their guns, trucks and equipment of all kinds onto the LST. We didn’t know where we would be taking them until we were under way.

After several days at sea we woke up one morning and there were ships of all kinds everywhere we looked. It was all big stuff so we knew that something big was coming up. These jarhead marines we had on board were typical marines. They bragged about how good they were with their anti-aircraft guns. We put them ashore and they set up their AA guns.

Tarawa was the toughest battle that we had had. There were one thousand and twenty six of our men killed plus many more wounded. There were 5,000 Japanese killed and only 18 taken prisoner. Our men were buried right away. Three days after the battle ended, the old man had to go ashore for some reason. My boat took him in and the stench of those rotting Japanese bodies that had been lying in the hot sun for three days was something I’ll never forget.

They dug a ditch with a bull dozer about 150 yards long and about 10 feet wide, then pushed all the dead Japs in it with the bull dozer. That afternoon we loaded 400 drums of high octane aviation gasoline on board. We beached the ship just as it was getting dark and had to wait until the next morning to unload it. That night about ten o’clock they sounded general quarters, the radar had picked up enemy bombers coming in. They would not let us fire our guns to keep from giving away our position all we could do was sit there and take it. If we had been hit with that four hundred drums of gas, it would have roasted us good. Our friends, the Marine Antiaircraft guys, got a good work out. They fired no telling how many rounds of ammo and never did hit one of the enemy. The next day when we asked them what happened, they admitted that their radar was calibrated 1000 yards off. They were firing behind them.

We stayed there for several days unloading freighters that could only anchor in the harbor. One of them had hundreds of cases of pineapple juice. I forget the guys name, but he and I stole several cases. We hid them in a void space that was sealed off. We filled a large glass bottle about three quarters full of pineapple juice, added enough sugar to almost fill it and then we sealed it and left it in the void space. About 3 weeks later we decided it should be ready. When we opened the void space, the fermenting stuff had built up pressure and the odor of the stuff floated back to the Crews Quarters. Those guys smelled it and followed their noses to where we were and, boy, did we have a party.

We finally loaded the survivors of the Second Marine amphibious and what was left of their equipment and took them to Hilo on the big island of Hawaii. We then went back to Pearl Harbor where we loaded men and equipment for what we later found to be Kwajelin in the Marshall Islands. The island is maybe 4 miles long and crescent shaped. We beached about the center of the island and had to stay there. There was a small island directly behind us where the army set up 105 mm howitzers that fired just over our heads. You had to duck every time one of them went over. Luckily they never did hit us. I later found out that it was my brother, Bunk’s 48th field artillery that was over there doing all the firing. I would have been really scared if I had known he had anything to do with it. —Harlee Gibbons